Image

Years ago, my dear friend and fellow journalist Rick Callahan pitched an article to a certain Indianapolis monthly magazine about Indiana Avenue. It was rejected.

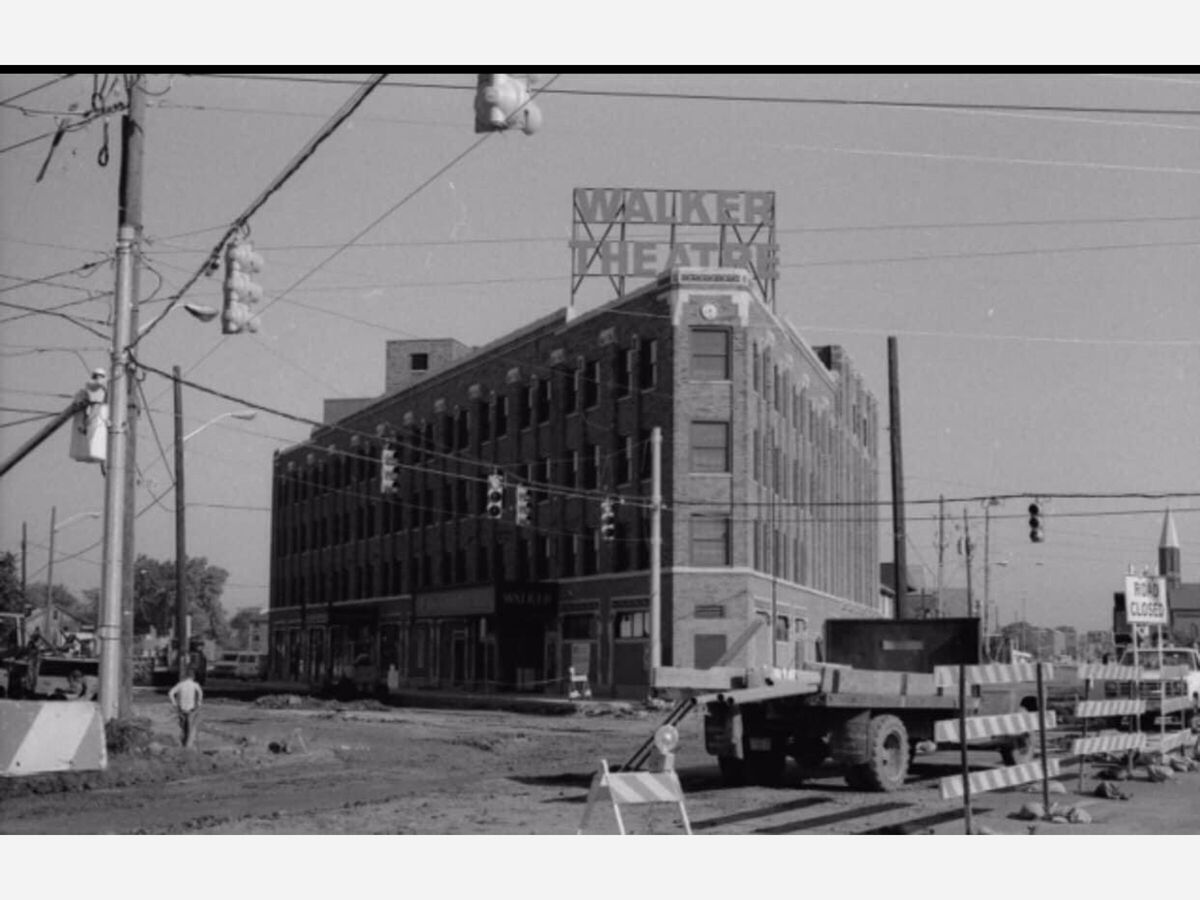

“Nobody wants to read about old jazz musicians,” the editor said. Rick disagreed and he was editor of the IUPUI student newspaper, the Sagamore, that year, so that’s where this originally appeared, in the late 1980s. He also took these black and white photographs, which document demolition around and on the Avenue. — Leslie

Jazz once king on 'Avenue'

By RICK CALLAHAN

Editor-in-Chief

Where Indiana Avenue meets Vermont Street not even a fragment of a foundation remains to attest to what once was.

Nearly 50 years ago, that intersection, just east of what would later become IUPUI, was the home of The Cotton Club, the crown jewel of Indiana Avenue. Put simply, Indiana's Cotton Club--not to be confused with New York City's version--was one of the few places in the city where blacks could gather for music, dance and laughs.

The Ritz Lounge, Dee's Paradise, The P and P Club and The Sunset were some of the others. "The Avenue,"as it was known, boasted blocks of swinging, flamboyant night spots. Most of these clubs had jazz bands on the first floor for those who wanted to sit back and listen, and dance bands on the second for the swingers.

One person who recalls the Avenue from its early beginnings is Marie Duewson, wife of Dewey Duewson, a bass violinist who once played with the Jimmy Coe Band, one of the city's famed big bands.

Mrs. Duewson, 71, left her parents’ farm in Anderson, Indiana in 1932 to look for a new and better life. Behind her she left her family, the clean country air, and a life of rural poverty.

She came with two second cousins to Indianapolis, resettling along The Avenue, and has been there since. The life she found was fast, fun and quite new.

"I came here for the Fourth of July and I'm still fourthing it," she muses.

"But I had fun. We were all poor, and all poor together. I learned how to drink here on the avenue. I learned how to bootleg too. And I learned how to live. It was a whole lot different than Anderson," Duewson says.

Her husband Dewey, 73, did not come to the city until the early 1940's, but quickly caught up on lost time. These days he prefers practicing his music to idle chit chat. His bass violin, an instrument several inches taller than himself, he has affectionately named "big Josie." He can often be found playing her at local churches with old buddies.

"The Avenue's still out there if you want to look for it. But you gotta look pretty far and hard. There isn't much left," he says.

Marie recalls her early days on the avenue as lean times. The Great Depression had left. the black community, already hard-pressed, experiencing a new extreme of financial woes. She held her own by doing "private work," scrubbing floors and cleaning the homes of better off whites for $3 a week.

"Money was so funny at that particular time, you see. You had to look real hard just to find a bad job.

It was just like what you heard the thirties were like," she says.

As a patron of The Avenue, Marie says she can attest to the fact that sometimes, especially during hot summer' nights, the steamy nightclubs would become so rowdy that they would spill out into the streets. The famed Cotton Club she recalls, had "the roughest clientele in town," and fights were commonplace. But she notes one prominent difference between violence then and today.

"People used to use their fists. They didn't use knives or guns," she says. "People loved each other then, even when they did fight. They would share, and look out for each other."

The Jazz State of Indiana, a book by Duncan Schiedt, describes yet another side of The Avenue--as a place where black and white musicians could gather to play music together, something that was viewed as unacceptable in those years before the civil rights movement.

"A sense of brotherhood existed among the players, and there was a constant exchange of musical technique and innovation," the book states.

However, like most cities in the Great Depression, it notes, Indianapolis had its share of shady characters. Bootleggers and racketeers were commonplace, and in many basements and alleys gambling and numbers games flourished. Schiedt's book mentions that two brothers, Tuffy and Joe Mitchell, had "interests" on the avenue. "Joe operated the Mitchellynne, a two-floor tavern on the west side of the street, while Tuffy busied himself with gambling interests," according to the book.

The "Hole-in-the-Wall," a dark, off-the-street joint was said to have been the roughest of the gambling sets. Shiedt's book says that another infamous spot, "The 'Blackstone'…so terrified a notorious guest, John Dillinger, one night, that he left quickly, preferring to take his chances out on the (avenue)."

Floyd Stone, president of Midtown Economic Development and Industrial Corporation (MEDIC), a not-for-profit organization that looks out for the interests of the community which surrounds Indiana Avenue, has other memories of the area. From 1937 to 1938, Stone, 69, operated the Jumbo Doughnut Shop at the corner of Senate Street and Indiana Avenue. He remembers serving shivering patrons hot coffee and glazed doughnuts on frosty winter mornings. His shop was strategically located less than 200 feet from one of the transfer spots of the city's once extensive streetcar system.

"I used to get a big crowd around six in the morning, when the early worm 'crowd was on their way to work. I'd come in at five and get the oil fired up and a bunch of rolls and doughnuts in the rising pans and wait for the transfer people," Stone says.

Despite these crowds, he said, his own inexperience with the nature of the business world caused the Jumbo Dougnut Shop to go bankrupt in less than two years. In 1938, at age 21, he closed the shop and moved on.

The only work available during that time for the black man, Stone said, was "work of the day," which is what he did until World War II broke out in 1941. Slowly, he, like other blacks, found better and more permanent jobs, Stone says, because of the void left by white workers who had been drafted. After the war he landed a job at Allison Gas Turbine Operations, where he remained until be retired in 1980.

Stone says that the reason the Avenue flourished, and indeed, even existed at all, was because blacks were driven there by the prejudices of the time. He says whites forced most blacks to live in one certain area of the city, and that was the area surrounding Indiana Avenue.

"It was the only real place that blacks had to their own. This was during the times of Jim Crow, remember. If you went south of Indianapolis you just flat ran into the straight out Jim Crow attitude. That kept a lot of people from moving around," he says.

Stone cites the civil rights movement and subsequent integration as the reason for the downfall of the Avenue.

Another former resident of the Midtown area, Russell Webster, agrees. Formerly a clarinet player in a jazz band called The Bobcats, Webster, 61, says that once the pressures of segregation were released, blacks naturally left the area to go to all the places they could never have gone before.

"With that type of pressure sure it drove people into one particular place. That's just where society put us in a hole and told us that's where we had to stay."

Russell says he is upset with the current development of downtown Indianapolis, saying that blacks are being driven out of the redeveloping inner city and into new slums. He is not very optimistic about plans on the drawing board for a possible rejuvenation of the Indiana Avenue area.

Another musician from that period, Clifford Henderson, formerly a tenor saxophonist in the Frank Reynolds' Band, says he would not want to bring the old days back even if he could. Henderson has lived along or near The Avenue since he was born in 1914, and has witnessed some of the darkest moments of racism in his days.

After he retired from his youthful days as a musician, he settled down in a steady job and married. He has remained both a visitor and musician on the Avenue since then, and watched it as it slowly fell to ruin.

By the early 1960's, he says, little remained to attract him there. But he has no bad feelings about his lost past.

''What's the use of staying in the past?" he says. "Blacks can't build their lives on what Madam Walker did.

"You can't bring back the ghost of the past, because along with it would come the racism, and all the bad stuff. That's gone and it will never be here again.”

© Rick Callahan